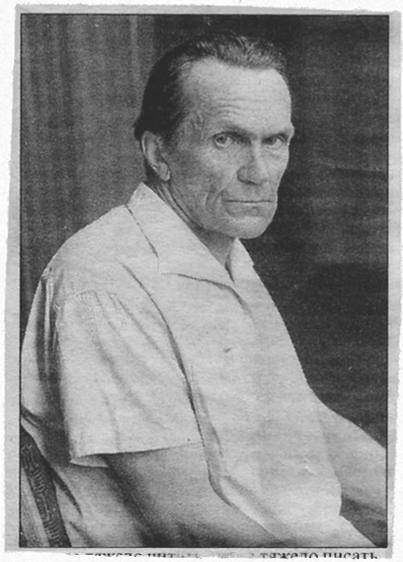

“My writing is no more about camps that St-Exupéry's is about the sky or Melville's, about the sea. My stories are basically advice to an individual on how to act in a crowd... [To be] not just further to the left than the left, but also more real than reality itself. For blood to be true and nameless.”.

Varlam Shalamov

Read about the goals of our project here.The first meeting with Shalamov:

- Varlam Shalamov “What I’ve seen and learned at Kolyma camps”

- Varlam Shalamov “The best praise”

- Irina Sirotinskaya “The Years We Talked”

- Valery Esipov “Varlam Shalamov and Alexander Solzhenitsyn”

On April 20-21 Uppsala Centre for Russian and Eurasian Studies (UCRS, Sweden) hosts an international symposium "The Gulag in Writings of Solzhenitsyn and Shalamov: Fact, Document, Fiction" (14 april 2017)

The symposium is organized by the UCRS, Dalarna University and University of Oslo. For more information see the Programme of the Symposium.Yasha Klots: “From Avvakum to Dostoevsky: Varlam Shalamov and Russian Narratives of Political Imprisonment” (23 february 2017)

Thus, in an extended sense, the entire tradition of Russian prison-camp writing since Avvakum is likened to a file of prisoners beating a path through the snow. Every author in this literary procession is also bound to play the role of a reader – of those who came before him, of times and places where s/he has not been. Throughout his own works, Shalamov consistently invokes his literary precursors and refers not only to Dostoevsky, as well as tsarist-time revolutionaries such as Vera Figner and Nikolai Morozov, but also to Avvakum, whose trace he follows in one of his most memorable poems, “Avvakum in Pustozersk”.Josefina Lundblad-Janjic's research on Varlam Shalamov’s one of the most important poems: “Аввакум в Пустозерске” (18 august 2014)

Shalamov considered his 1955 poem «Аввакум в Пустозерске», composed two years after his return from the camps of Kolyma, one of his most important poems. He also considered the poem, written in amphibrachic dimeter and composed of thirty seven four-line stanzas, to unite the “historical figure” of the seventeenth-century schismatic archpriest Avvakum with elements of “the author’s biography.” Read as an allegory, the poem appears to deal with the violent oppression in the twentieth century which Shalamov personally experienced: the terror under Stalin. A self-proclaimed atheist, Shalamov endows the historical figure of Avvakum not solely with religious but also with political significance: the archpriest of his poem becomes a prominent representative of Russian resistance to the abuse of power. Through the use of allegory, “a place where the political can meet the aesthetic,” Shalamov creates a lyric which, as Avvakum did through his Autobiography three hundred years prior, presents not only a challenge to contemporary society but also an alternative perspective on its most recent past.Josefina Lundblad's Account of the 2013 Conference in Prague (18 may 2014)

«This year’s International Shalamov Conference made the daring move from theory to practice in a most literal manner: from discussing literary works about the Gulag to visiting the physical site of an actual camp, Vojna, an experience that left all of us deeply moved».Robert Chandler: “The poetry of Varlam Shalamov (1907-82)” (21 march 2014)

Varlam Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales is generally recognised — at least by Russians and readers of Russian — as a masterpiece of Russian prose and the greatest work of literature about the Gulag; this thousand-page cycle of stories draws mainly on Shalamov’s experiences as a prisoner in Kolyma, a vast area in the far northeast of the USSR that, throughout most of the Stalin era, was in effect a mini-State run by the NKVD; most of the inmates of its hundreds of camps were either felling trees or mining coal or gold. Shalamov’s poetry, however, still has few readers even in Russia, although he himself seems to have valued it above his prose.Lysander Jaffe, a student at Williams College (USA) compares two English translations of Shalamov in his article “Writing as a Stranger:” Two Translations of Shalamov’s “The Snake Charmer” (20 june 2013)

“What does it mean, then, to retell “The Snake Charmer” in another language? For translators, this challenge has proven formidable, not least because of the original text’s long, convoluted history of publication. “The Snake Charmer” and other Kolyma Tales first appeared in the Russian émigré journal Novyi Zhurnal in 1967, and was not re-published until 1978. The 1967 version differs drastically from all subsequent versions, omitting significant portions of Shalamov’s prose. John Glad first translated this and other Kolyma Tales into English in 1980, and his translation reflects many of these omissions. Glaring inaccuracies also result from the many typos in the 1967 version; the most unfortunate of these is the line “Эх, скука, ночи длинные,” written as “Эх, скука, ноги длинные” in the first publication, and rendered by Glad as “It’s so boring my legs are getting longer.” (my italics) It may be argued that on a small scale, Glad was working from a different original than Robert Chandler and Nathan Wilkinson, who re-translated “The Snake Charmer” almost thirty years later.”A panel entitled “Shalamov as a Revolutionary” has been accepted for the ASEEES 45th Annual Convention, which will be held in Boston in November 2013 (6 april 2013)

The following scholars will participate in the panel: Elena Mikhailik (University of New South Wales, Australia), Olga Cooke (Texas A&M University, USA), Josefina Lundblad (University of California at Berkeley, USA), Michael Nicholson (Oxford University, UK), and Reed Johnson (University of Virginia, USA). The conference will take place November 21-24 in Boston, MA“Shalamov”, Valery Esipov's new book, is now available in stores nationwide (14 august 2012)

First chapters are presented online at russ.ru.The “Duck”, translated by Robert Chandler & Nathan Wilkinson (5 june 2012)

“It had been very difficult for the man to take a decision himself, to act independently, to do something his daily life had not prepared him for. He had not been taught to hunt ducks. That was why his movements had been helpless, clumsy. He hadn’t been taught to think about the possibility of such a hunt — his brain couldn’t come up with correct answers to the unexpected questions life posed. He had been taught to live differently, without needing to take decisions of his own, with another will — someone else’s will — in charge of events. It is uncommonly difficult to meddle in one’s own fate, to ‘refract’ fate. And maybe that’s all for the best — a duck dies on a patch of water, a man in a barrack.”Robert Chandler's & Nathan Wilkinson's translations of three short stories by Shalamov (9 may 2012)

In the late 70s, Robert Chandler has published translations of several short stories by Shalamov (including “Sherry Brandy”, “Berries” and “Duck”) in magazines “Index on Censorship” and “Bananas”. In the anthology “Russian Short Stories from Pushkin to Buida” (Penguin Classics, 2006) he has included the following new translations on which he collaborated with Nathan Wilkinson: “Through the Snow”, “Berries”, “The Snake Charmer”, “Duck”.

News archive: 2017, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2009

The copyright to the contents of this site is held either by shalamov.ru or by the individual authors, and none of the material may be used elsewhere without written permission. The copyright to Shalamov’s work is held by Alexander Rigosik. For all enquiries, please contact ed@shlamov.ru.